|

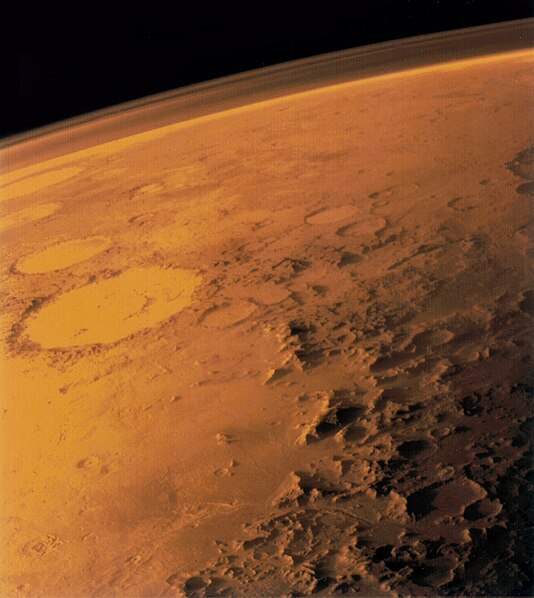

| Tenuous atmosphere of Mars visible from low orbit |

Although Krauss makes a reasonable technical case for this unconventional scheme, his ethical analysis it is scant, relying, more or less, on this anecdote,

"One of my peers in Arizona recently accompanied a group of scientists and engineers from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory on a geological field trip. During the day, he asked how many would be willing to go on a one-way mission into space. Every member of the group raised his hand. The lure of space travel remains intoxicating for a generation brought up on Star Trek and Star Wars."

|

| "Jackass: The Movie" movie poster |

Don't get me wrong, I was one of the generation that Krauss mentions; intoxicated by Star Trek - although less so by Star Wars - and, for the better part of my life I, too, would have eagerly raised my hand to volunteer to become a Mars pioneer, naively confident that my exuberance at the outset of such an adventure would immunize me against any hardship I encountered, no matter its duration or its severity. But I have lived long enough to realize that even the most passionately declared vows fall victim to the realities of time and circumstance, and that we turn out to be very poor prognosticators of our own capacity to persevere, especially in the face of chronic psychological insult. I imagine that Lawrence Krauss has lived long enough to have come to this realization as well.

Taken aback by Krauss's opinion piece, I submitted the following (unpublished) letter to the Times in response.

To the Editor:

Lawrence Krauss may have come up with a correct engineering solution for getting human beings to Mars by dispatching volunteers on a one-way trip, but he falls short as far as the analysis of the ethical implications are concerned.

No doubt there are many who would volunteer for such a seemingly marvelous expedition. But will they in any realistic way be able to anticipate the emotional hardship that they will have to endure? And how will we feel, having exploited their naive enthusiasm, forced to watch from a distance of more than 35 million miles, as they descend into likely depression and inevitable old age, unable to offer the consoling touch of a human hand?

Marc Merlin

Atlanta

First and foremost I take issue with Krauss's presumption that voluntary participation in a research study - and the one-way trip is proposed in order to conduct scientific research - relieves investigators of their ethical responsibility to protect the health and welfare, emotional and physical, of the subjects that they have recruited. I also wonder what could possibly constitute "informed consent" in deciding to expose people to, not only unprecedented circumstances of emotional hardship, but ones of unprecedented duration.

It would be one thing to tell enthusiastic volunteers, "you are going on a one-way trip to Mars for the advancement of science" and quite another to say, "you are going on a one-trip to Mars for the advancement of science, and you will be undergoing the kind of isolation and confinement, away from sources of solace and companionship, that may very well will leave you depressed, perhaps insane or suicidal, within a matter of months; that you and at most a handful of colleagues will be confined to close quarters for years, even decades, without the possibility of the briefest separation; that you will never again enjoy a stroll through a garden in springtime or a dinner out with friends at a favorite restaurant. "

|

| Magellan's ship Victoria, detail from a map of Ortelius (1590) |

Before we endorse the Mars mission they propose, we should convince ourselves that we aren't consigning noble volunteers to (short) lives suffused with sadness and torment. Their initial excitement about serving the grand interests of science cannot immunize them from these possible outcomes, no matter what they say or hope.

Afterword

It may come as a surprise to readers of this series that I do not oppose the manned exploration and eventual colonization of Mars. I imagine that, barring a collapse of our global civilization, it will begin sometime in the latter half of this century or early in the next one. This will mark a wonderful turning point in human history!

What I do oppose is the manufactured urgency that surrounds the proposed one-way mission to Mars; that it is a necessary component in our scientific investigations of that planet; that it is a critical step to insure our survival as a species; that it will in any way offer a common purpose which will help to remedy political disunion and conflict here on Earth.

|

| Empty bottle with mail (credit: Larry Yuma) |

As a message in a digital bottle of sorts to those first unharried one-way pioneers who will become the first long-term inhabitants of the Red Planet, I want to say from decades past how much I admire you for your courage, since I know that even the most carefully planned space missions will never eliminate risks to life and limb. And I want to thank you for your willingness to endure hardship, especially the first among you to arrive, since the going will be particularly rough for you. But I take consolation in imagining that your isolation will be short lived and that you will be buoyed in your work knowing that you are preparing the ground for a larger number of compatriots who will be arriving soon after you do, allowing you to once again assume your role in the ranks of a human community large enough and vibrant enough to ensure your emotional and psychological well-being as your bold colony grows and thrives.

May you live long and prosper!

One-Way Mission to Mars - Ethics Fail by Marc Merlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.