This is the introduction to a multi-part critique of a proposal that has been under consideration the last couple of years to send human pioneers on a one-way trip to Mars.

In Steven Spielberg's 1997 science-fiction film

The Lost World: Jurassic Park chaos theorist Ian Malcolm, commenting on the decision to move genetically-resurrected dinosaurs off the island where they have been safely contained, says to the scientist-entrepreneur responsible for creating the creatures and placing them in a theme park, that this "is the worst idea in the long, sad history of bad ideas and I'm going to be there when you learn that."

When I read an op-ed piece in the

New York Times by physicist Lawrence Krauss at the end of August, 2009 proposing

A One-Way Ticket to Mars, I was reminded that the history of bad ideas marches on, specifically those bad ideas derived from a technological vision of the future not anchored in human reality. Of course, bad ideas come and bad ideas go, but this one appears to have legs, as the publication in November of this study,

To Boldly Go: A One-Way Human Mission to Mars, by Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Paul Davies in

The Journal of Cosmology would indicate.

Having little hope of being around myself when and if this ill-considered idea is implemented, much less when it either reaches fruition or unravels, I take the opportunity to state my objections now.

Why a one-way trip?

|

John Kennedy before a joint session

of Congress, May 25, 1961 |

The proposal of a one-way Mars mission is not without technical merit. Our 50 years of space-faring experience have equipped us with the engineering know-how to get human beings to the surface of Mars. But unlike John Kennedy's

speech before Congress in 1961 calling on Americans to take up the challenge of landing men on the Moon by the end of the decade, the possibility of returning these explorers of this new frontier safely to Earth made exceed our financial, if not our technological, grasp.

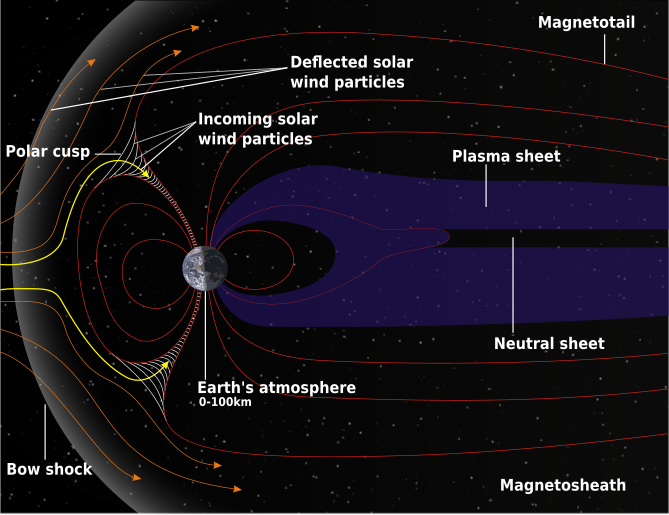

|

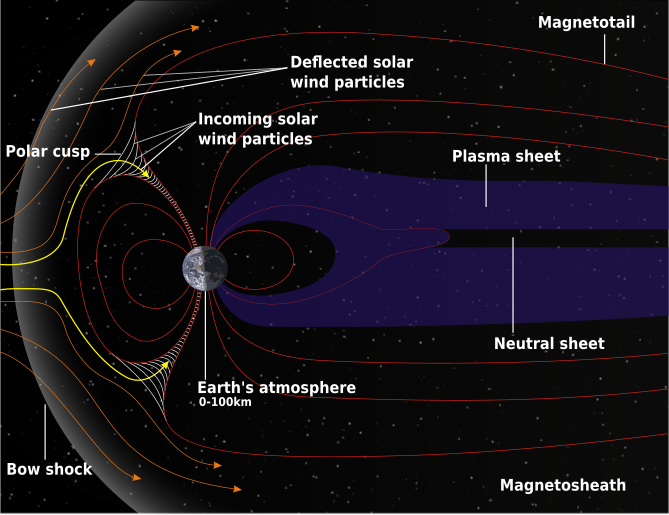

Schematic of the Earth's magnetosphere

with the solar wind flowing from the left |

The primary reason for this has to do with the fact that outside the protective envelope of the Earth's

magnetosphere, astronauts are exposed continuously worrisome levels of background cosmic radiation and occasionally to devastating levels inflicted by solar flares. Tolerable risks associated with brief excursions to the Moon by the Apollo astronauts become unacceptable ones when spaces voyages extend for many months, as would be required by a round-trip mission to Mars. Unacceptable that is if conventional safety recommendations concerning radiation exposure are at all respected.

As we might guess from the lead-lined aprons that are provided for our protection when we undergo dental x-rays, there are indeed ways to shield passengers during a long space voyage. Unfortunately the increase in the weight of a spaceship by including such shielding adds significantly to the cost of the mission. To make matters worse, the weight of fuel and provisions required by a two-way trip make the cost even more prohibitive, at least in our contemporary political and fiscal climate. So, first and foremost, a one-way journey is proposed to reduce the cost of a manned Mars mission, with the intention of putting it within practical reach relatively soon.

|

2001: A Space Odyssey anticipated

challenges posed by long-duration

space flight |

The approach avoids another problematic consequence of long-duration space travel, namely the lengthy rehabilitation required for astronauts to adjust to Earth's gravity that is a result of their extended stay in reduced- or zero-gee environments. In addition, the risks to life and limb associated with taking off from Mars, reentering the Earth's atmosphere and landing here are eliminated by a one-way mission, not to mention the additional weight penalties required by the spacecraft systems responsible for accomplishing those demanding tasks.

Motivations for a Mars colony

According to the authors there are several motivations for the establishment of a permanent human presence on Mars, whether using a one-way Mars mission as a kick-start or not. They are in brief:

- to offer humanity a "lifeboat" in the event of a mega-catastrophe here on Earth,

- to provide a base of operations for the scientific study of Mars, especially in the search for life forms that it might harbor, and a springboard for exploration of the outer solar system,

- and to serve as a "strong and uplifting theme for all of humanity" with all the political and social benefits that would supposedly imply.

I would concur, that each of these reasons is good - even noble - on its face. It is not at all clear, though, that these objectives can not be accomplished - perhaps better accomplished - using alternative approaches, at far lower cost and with far less risk to human life.

General Reservations

That said, my criticisms of the scheme outlined in the Schulze-Makuch / Davies paper have less to do with whether a one-way mission achieves their stated limited technical goals, and more to do with whether it represents either a cost-effective or an ethical way to go about colonizing or even exploring Mars. I am also skeptical whether the imagined urgency that drives their dubious solution is in the least bit well-founded. These will be the concerns that I will address in the parts of this essay to follow.

Does a One-Way Mission to Mars Make Sense? - Introduction

Does a One-Way Mission to Mars Make Sense? - Introduction by

Marc Merlin is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at

thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.