This essay on the movie Self/less contains spoilers.

As the movie Self/less opens, we meet Damian Hale (Ben Kingsley), a master of the business universe, if there ever was one. Damian takes no time in demonstrating that he is not about to be fooled or out maneuvered. Losing is not an option for him.

But we soon learn that it looks like this never-say-die competitor, may have finally met his match. Death is knocking on Damian’s door, and it isn’t inclined to take “no” for an answer. Might there be a way for Damian to use his smarts and enormous wealth to win again this time around?

It turns out that, thanks to an entrepreneur-inventor named Albright (Matthew Goode), “life’s a bitch and then you die,” is a restriction that now applies only to the undeserving 99.99%. Albright has developed a technology that allows extraordinarily rich guys like Damian to “shed” their old, faltering bodies and have their consciousnesses transferred into young, robust ones.

After a bit of reflection and a ham-handed attempt to make amends with his estranged daughter, Damian decides to pay his money and take his chances. When Albright’s spinning MRI scanners come to a stop, Damian’s consciousness winds up inside the body of someone who looks a lot like Ryan Reynolds (Ryan Reynolds). Damian, it would appear, has hit the lab-grown body jackpot.

At first the consciousness transfer seems to have come off without a hitch. There is a lengthy montage, reminiscent of a Rocky movie, that shows post-transfer Damian training hard to master the challenges that come with controlling his exquisite, new body. But, fighter that he is, Damian is more than up to the rehabilitation tasks. Vivid flashbacks, though, intrude on Damian’s experience and remind us that all is not right in his brave, new Reynoldsian world.

Sadly, the procedure has not gone well at all when it comes to acting. It ends up feeling like someone forgot to hook up the “personality” cable that connected Damian’s old body with his new one for the consciousness transfer.

The old Damian may have been a crusty old son of a bitch, but in the short period of time that he has on screen, Kingsley somehow lets us know that he is also a complex man who has known ample amounts of both pride and regret during the course of his life.

As portrayed by Reynolds, the young Damian never seems to emerge fully from the confused state of mind that immediately follows the consciousness transfer. Sure, over the course of the movie he winds up showing that he is still a smart adversary and a relentless competitor, but none of the texture of the character handed off to him by Kingsley survives.

The film itself has been promoted as a thought-provoking science fiction thriller that allows us to contemplate the possibility that technology may soon provide a way for us to live forever, while forcing us to consider the moral price that we might pay in doing so. Yet, as with most science fiction, the new-fangled science is only incidental to the retelling of an older, venerated story.

In this case of Self/less, this storyline is a deal with the devil. Here Damian takes on the role of an essentially noble but arrogant Faust and Albright his obsequious and beguiling Mephistopheles. The movie reminds us yet again that striking a bargain to sell one’s soul is never without unanticipated consequences.

It’s also interesting to consider is how Self/less borrows from other genres.

As it turns out, Damian’s consciousness has not just landed in a buff, young body, but it’s the buff, young body of an superbly trained U.S. Army Special Forces soldier. Although the soldier’s still resident conscious awareness is suppressed by medication, his killing instincts kick in reflexively whenever they are needed, and they are needed a lot in the movie.

In this regard the film feels a little like a variation of the action-thriller The Bourne Identity — may be it could be called The Reborn Identity? — in which the hero, a superbly trained C.I.A. killing machine, has lost all conscious memory of his former life as a spy, but is able to draw reflexively on his martial arts skills and detailed knowledge of spycraft to save the day, in spite of his otherwise complete amnesia.

But at its heart, Self/less harkens back to the genre of “second-chance” stories, such as It’s a Wonderful Life, in which death is held at bay, at least briefly, so that the protagonist can return to the world to set things right.

A classic example of this genre is Warren Beatty’s 1978 Heaven Can Wait. In that movie, Beatty’s nice-guy quarterback hero, Joe Pendleton, is snatched up to heaven before his time, and, as a result, must be parked in the body of a no-good tycoon, Leo Farnsworth, until a more suitable one can be found. This celestial mix-up creates an opportunity for Joe to right some of Leo’s corporate wrongs, fall in love with a beautiful woman played by Julie Christie, and win the Superbowl. Not bad at all as far as second chances go.

Given how religious sensibilities have changed in the last forty years, with Self/less it is oblivion, not heaven, that must wait. And Damian’s unfinished work is not all that glorious: it’s simply to rediscover the importance of family and to repair his relationship with his daughter as best he can from beyond the grave. Undoing the nefarious body-snatching enterprise that Albright has set in motion would complete his redemption.

Young Damian does succeed in his second-chance mission. My biggest regret is that old Damian, as portrayed by Ben Kingsley, was not along for the ride.

Essays emerging from my varied interests in science, film, politics and philosophy, among other things.

Showing posts with label critique. Show all posts

Showing posts with label critique. Show all posts

Saturday, July 4, 2015

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

"Two Days, One Night" - Norma Rae in retreat

Imagine you're in the open ocean drowning and the only thing you can do to get your head above water is to grab ahold of the feet of the companions a few feet above you who are kicking as hard as they can to draw a breath of air. They may be able to rescue you if they work together, but it's possible, even if they try, that they will be pulled under. What can you ask of them? What sacrifice are they obligated to make to help save your life?

This scene captures much of Sandra's (Marion Cotillard) situation at the opening of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne's film Two Days, One Night. About to return from disability leave from her job at a small solar panel manufacturing plant in Belgium, Sandra learns that the manager of the factory, M. Dumont, has offered her sixteen co-workers a Faustian bargain of sorts: they can vote to allow Sandra to return to work as before, or they can vote to have her laid off and, as a consequence, each reap a €1,000 bonus.

A vote, taken on the Friday before Sandra is scheduled to return, goes 15-1 against her. But she learns from her one faithful supporter, Julliette, that it has been tainted by the meddling of the plant's foreman. Devastated by the bad news and still beaten down by the depression that has led to her absence from work, it is all Sandra can do to do to get out of bed and to go with Juliette to the plant and plead with Dumont for a makeover vote.

Backing his car out of the parking lot, eager to head home for the weekend, M. Dumont relents and agrees to a second vote on Monday. And thus begins Sandra's two days and one night, the time she has to convince her co-workers to vote to give up their bonus pay so that she can keep her job.

The movie then unfolds as series of tense encounters, as Sandra locates each of them to make her case to stay employed. These typically begin with a knock on the door in a working class neighborhood and a puzzled, but polite, welcome by the co-worker himself or a wife or a child. Each of her pleas becomes an affecting drama in its own right. And Cotillard uses these dramatic moments to display her impressive power as an actor.

But what is most remarkable about Two Days is its unelaborated upon backstory. Globalization and its impact on advanced, once worker-oriented economies of Western Europe is the elephant in the room. Sandra's company, faced with stiff competition from a Chinese solar competitor, is fighting for its financial life and is determined to do so on the backs of its employees.

The unsettling premise of the film is that, when faced with obvious manipulation by management designed to extract concessions from employees and sow dissension in their ranks, workers roll over without complaint. No demands are made for sacrifices from M. Dumont, his higher-ups, or, God forbid, the shareholders of the company. Sandra and her co-workers accept these indignities matter of factly and then proceed to fight among themselves over scraps from the master's table.

The unsettling premise of the film is that, when faced with obvious manipulation by management designed to extract concessions from employees and sow dissension in their ranks, workers roll over without complaint. No demands are made for sacrifices from M. Dumont, his higher-ups, or, God forbid, the shareholders of the company. Sandra and her co-workers accept these indignities matter of factly and then proceed to fight among themselves over scraps from the master's table.

In another age, Marion Cotillard, certainly more than beautiful enough, would have played a latter-day Marianne, leading the charge of the economically dispossessed to the barricades to turn back corporate greed, or a Belgian Norma Rae, rallying workers to unite in pursuit of their common economic cause. Instead Sandra's struggle, as compelling as it is as portrayed by Cotillard in Two Days, One Night, is directed solely at her inward demons and not at those roaming unchecked in the outside world.

This scene captures much of Sandra's (Marion Cotillard) situation at the opening of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne's film Two Days, One Night. About to return from disability leave from her job at a small solar panel manufacturing plant in Belgium, Sandra learns that the manager of the factory, M. Dumont, has offered her sixteen co-workers a Faustian bargain of sorts: they can vote to allow Sandra to return to work as before, or they can vote to have her laid off and, as a consequence, each reap a €1,000 bonus.

A vote, taken on the Friday before Sandra is scheduled to return, goes 15-1 against her. But she learns from her one faithful supporter, Julliette, that it has been tainted by the meddling of the plant's foreman. Devastated by the bad news and still beaten down by the depression that has led to her absence from work, it is all Sandra can do to do to get out of bed and to go with Juliette to the plant and plead with Dumont for a makeover vote.

Backing his car out of the parking lot, eager to head home for the weekend, M. Dumont relents and agrees to a second vote on Monday. And thus begins Sandra's two days and one night, the time she has to convince her co-workers to vote to give up their bonus pay so that she can keep her job.

The movie then unfolds as series of tense encounters, as Sandra locates each of them to make her case to stay employed. These typically begin with a knock on the door in a working class neighborhood and a puzzled, but polite, welcome by the co-worker himself or a wife or a child. Each of her pleas becomes an affecting drama in its own right. And Cotillard uses these dramatic moments to display her impressive power as an actor.

But what is most remarkable about Two Days is its unelaborated upon backstory. Globalization and its impact on advanced, once worker-oriented economies of Western Europe is the elephant in the room. Sandra's company, faced with stiff competition from a Chinese solar competitor, is fighting for its financial life and is determined to do so on the backs of its employees.

The unsettling premise of the film is that, when faced with obvious manipulation by management designed to extract concessions from employees and sow dissension in their ranks, workers roll over without complaint. No demands are made for sacrifices from M. Dumont, his higher-ups, or, God forbid, the shareholders of the company. Sandra and her co-workers accept these indignities matter of factly and then proceed to fight among themselves over scraps from the master's table.

The unsettling premise of the film is that, when faced with obvious manipulation by management designed to extract concessions from employees and sow dissension in their ranks, workers roll over without complaint. No demands are made for sacrifices from M. Dumont, his higher-ups, or, God forbid, the shareholders of the company. Sandra and her co-workers accept these indignities matter of factly and then proceed to fight among themselves over scraps from the master's table.In another age, Marion Cotillard, certainly more than beautiful enough, would have played a latter-day Marianne, leading the charge of the economically dispossessed to the barricades to turn back corporate greed, or a Belgian Norma Rae, rallying workers to unite in pursuit of their common economic cause. Instead Sandra's struggle, as compelling as it is as portrayed by Cotillard in Two Days, One Night, is directed solely at her inward demons and not at those roaming unchecked in the outside world.

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Luc Besson's "Lucy" - Girl Gone Transhuman

Avast, there be spoilers here!

When we first meet her, Lucy is a party-girl living an apparently carefree life in Taiwan. That is until her low-life boyfriend handcuffs her to a briefcase loaded with a new recreational superdrug CPH4 and, without her knowledge, dispatches her into the lions’ den of a murderous, transnational Korean nacro-gang headed by Mr. Jang (Min-sik Choi). Mr. Jang, it turns out, has designs on Lucy’s body, not in the usual way, but as a covert system to deliver CPH4 to one of a number of far-flung distribution points on the globe.

Not surprisingly, things don't go as either Mr. Jang or Lucy expect, and soon CPH4 leaking into Lucy’s abdominal cavity begins to work its chemical magic on her brain. After crawling around on the ceiling in a frenzy in a scene reminiscent of the “Exorcist,” a frightened, whimpering Lucy calms down considerably and, realizing that her survival depends on her recovering the rest of Mr. Jang’s CPH4, sets out on a bloody journey that includes sticking it to Mr. Jang in more ways than one.

This all could be a nice premise for a well-conceived science-fiction action-thriller, which “Lucy” is not. Instead, the writer-director Luc Besson imbeds this good idea in a lot of sciencey drivel and tries to anchor Lucy’s transformation from human to more-than-human in a relationship that develops between her and researcher and neuroscience god, Professor Samuel Norman (Morgan Freeman).

We are introduced to Professor Norman when he stands before a rapt assembly of neuroscientists lecturing them about the factoid that humans are at the pinnacle of biological evolution, since they alone have been able to tap into as much as 10% of their mental capacity. (The percent-of-our-brains trope is put to much better use in Albert Brooks’ “Defending Your Life.”) Not content with sharing just that piece of misinformation, Norman goes on to ponder the wondrous (and impossible) things that may come when we progress as a species to using a larger and larger fraction of the neurons we have squirming around in our noggins.

It’s hard to say what’s more disturbing in these scenes, the continued propagation of this silly and unfounded 10% myth about the human brain, or the repeated cuts to Professor Norman’s slavish audience, hanging on his every word as though they were his winged-monkey minion waiting for a command to do his bidding.

My gripe here is not with suspension of disbelief. As I've discussed in another blog post, all sorts of silly ideas can be employed effectively as premises to set science-fiction stories into motion. But, like good supporting actors, these counterfactual elements should introduce themselves early in the performance and then step out of the limelight to give the principal performers plenty of room. Instead, in “Lucy” the percent-of-our-brains canard insists on hanging around near center stage. We get hit over the head with it time and time again as Mr. Besson reminds us exactly where Lucy is in her brain-fraction progression, ticking off the percentages like some sort of thermometer in a public television fundraising drive.

What’s missing in all this is the dramatic tension that, by all rights, should be at the core of this story and that is how Lucy’s headlong rush toward mental perfection necessitates the withering away of her emotional self. And, by all rights, Lucy’s anchor in the world of human affairs, should not have been the distant and avuncular Professor Norman, but her flesh-and-blood (and sexy) companion, Pierre Del Rio (Amr Waked), the French police inspector, who reluctantly takes up her cause but eventually becomes her committed friend and ally.

The connection between Lucy and Del Rio is suggested when she explains with a kiss why she is keeping him as a companion, even though she has grown so powerful that she doesn't need his help anymore. But, sadly, this relationship is hardly developed, in spite of what appears to be a serviceable chemistry between Johansson and Waked. The result is that a taut and suspenseful film featuring these two characters at its center is saddled with a subplot that, from what I can tell, only serves to bring Morgan Freeman into the picture to underwrite its box-office success.

More disappointing, though, is how poorly Scarlett Johansson is utilized in the title role. Her transition from human to beyond-human happens far too quickly. A brief phone call with her mother early on serves as a requiem for the life that Lucy is leaving behind as she is impelled, like it or not, toward transcendence. What should have been a wrenching and soul-searching second act of the movie is relegated to little more than one scene. And, although Johansson uses the limited time to good effect, it offers her short shrift as far as real acting goes.

So, after a well-executed turn as a helpless and frightened young woman at the beginning of the movie, Johansson takes on the mien of the soulless automaton that Lucy is fated to become. Aloof, with wide eyes and fixed gaze, she marches zombie-like through the remainder of the film toward Lucy's inevitable godhead. There’s not much acting for Johansson to do here.

How this lapse in attention to his main character may have come about is suggested by the “meaning of life” revelation that Lucy delivers just before her apotheosis. As she travels to the distant past and masters the progression time, moving people backward and forward in Times Square at whim, Lucy comes to the realization that time itself is the central element of our reality, whatever that might mean.

The movie's title “Lucy” refers to a hominid ancestor of ours that lived in Africa’s Afar Triangle some 3 million years ago, it also bears resemblance to the director's own name, Luc. Perhaps Besson is reminding us of the power that he has as a writer-director in manipulating the way a film unfolds, rapidly moving his characters backward and forward in time with God-like ease. That’s all well and good, but he should remember that it’s nice to slow down and get to know them better in all the commotion.

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

One-Way Mission to Mars - Kumbaya Fail

In this fourth part of my critique of a recently proposed one-way mission to Mars I address whether a kick-start colonization of Mars can be justified on political grounds. My third post disputes whether such a colony is either a safe or a cost-effective way to pursue important scientific goals. You can find the introduction to the series here.

I came of age during the the Apollo program and, as a 14-year old, watched enraptured as Neil Armstrong placed his booted foot on lunar soil. Old enough to appreciate what this meant as a national achievement and as an engineering tour de force, I was also old enough to be aware of the promise that it offered to be a unifying force for "all mankind", one beautifully anticipated in the earthrise Christmas Eve image taken by the astronauts of Apollo 8 less than a year before.

Although that day in July 1969 was celebrated the world over, the moon landings themselves failed to have any long-term impact as far as bringing people closer together. The Cold War and its proxy conflicts raged on, indifferent to these wondrous technological achievements.

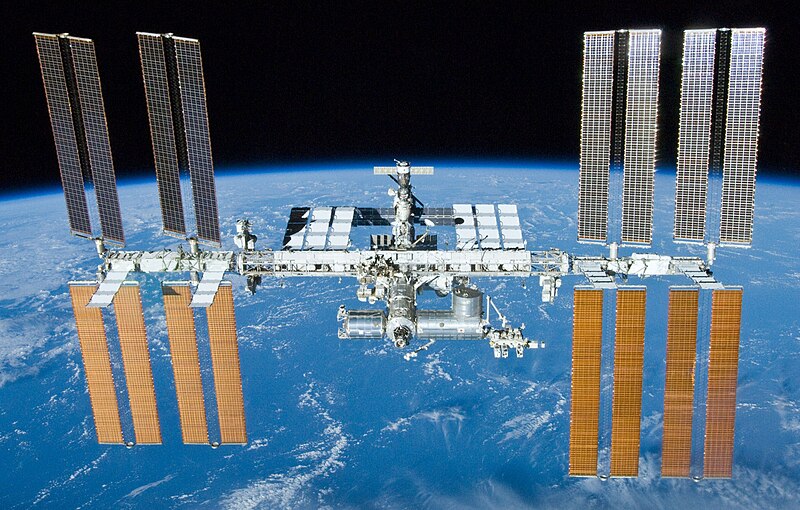

Another example of an unmet promise of political uplift offered by a costly space mission, this one closer to home, is that embodied by the International Space Station (ISS). Touted as a permanent multicultural and multinational human presence in low-earth orbit, it, too, was to provide Earth-bound humans with a transcendent unifying theme.

Yet, resplendent, orbiting above the planet at an altitude of 350 km (220 miles), it goes largely unnoticed by the world below. This is not to say that the Space Station has not called into being a remarkable intergovernmental collaboration on an unprecedented scale, but to note that, although an engineering triumph, it has resulted in few if any discernible "major beneficial political and social implications" of the type advertised by the one-way Mars mission proposal. If the tepid public reaction to the ISS is any indication, then it's not clear that such expectations should weigh in favorably in our evaluation of Schulze-Makuch and Davies's scheme to establish a human settlement on Mars post haste.

As with other motivations for the proposed expedited colonization of Mars - that it serve as a science outpost and as a lifeboat for humanity - rational analysis demands that we consider how alternative approaches compare as far as promoting a more positive political and social climate here on Earth. In other words, given that a one-way mission would cost hundreds of billions of dollars or more, how might similar - or even significantly smaller sums - be spent to foster feelings of union and brotherhood.

Although little can be done directly to bridge the divides of malignant ideologies, religious fanaticism and misguided nationalism that separate us, it has been long understood the alleviation of much of human suffering is within our grasp and that the result of doing so would yield unquestionable major political and social benefits. An example of an immediately attainable objective would be the eradication of endemic diseases such as guinea worm. A more ambitious challenge would be to commit to insure that every person on the planet is provided with adequate daily nutrition as well as access to a reliable source of drinking water.

Without a doubt, goals such as these are politically daunting, but they are technically and economically feasible, particularly if countries like the United States expand their vision of international security - and with it the application of their annual one trillion dollars of "defense" spending - to encompass important non-military threats to world order and human well-being. Indeed, mobilizing the nations of the planet to mitigate the damage anticipated as a result of disruptive climate change this century, provides a ready-made unifying goal for humanity, one which we are morally obligated to address and, to the extent that we prevail in our efforts, one which could both unite and ennoble us.

Suffice it to say, we don't need to go shopping around for extraterrestrial projects, such as an ill-considered one-way mission to Mars, in order to concoct challenges to inspire and unify us, when working in broad international coalitions against terrestrial scourges, such as disease, hunger, global warming, not only would generate a much greater sense of unity and common purpose, but also would offer desperately needed material advances to billions of people here on Earth.

Part 5: One-Way Mission to Mars - Ethics Fail

One-Way Mission to Mars - Kumbaya Fail by Marc Merlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.

In their November 2010 paper in the Journal of Cosmology, along with other reasons for pursuing an expedited one-way mission to Mars, Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Paul Davies assert that

establishing a permanent multicultural and multinational human presence on another world would have a major beneficial political and social implications for Earth, and serve as a strong unifying and uplifting theme for all humanity.

It is hard to see how they derive confidence in such a claim.

|

| Independence Day movie poster |

Space and space missions are a standard of science fiction when it comes to creating story lines that unite humanity in spite of centuries-old divisions. This unification is often accomplished most efficiently when planet Earth is in imminent danger of being destroyed by an asteroid impact or being conquered by an alien armada.

Nowhere is this better exemplified than at the climax of the 1996 movie Independence Day, where the American president, played by Bill Pullman, delivers a speech that rallies his troops for a last-ditch airborne counterattack on an invading force, with identical calls to arms being enacted simultaneously around the globe by people of all races and all creeds and all colors, apparently.

Nowhere is this better exemplified than at the climax of the 1996 movie Independence Day, where the American president, played by Bill Pullman, delivers a speech that rallies his troops for a last-ditch airborne counterattack on an invading force, with identical calls to arms being enacted simultaneously around the globe by people of all races and all creeds and all colors, apparently.

|

| Earthrise, December 1968 |

Although that day in July 1969 was celebrated the world over, the moon landings themselves failed to have any long-term impact as far as bringing people closer together. The Cold War and its proxy conflicts raged on, indifferent to these wondrous technological achievements.

|

| International Space Station from the Space Shuttle Atlantis |

Yet, resplendent, orbiting above the planet at an altitude of 350 km (220 miles), it goes largely unnoticed by the world below. This is not to say that the Space Station has not called into being a remarkable intergovernmental collaboration on an unprecedented scale, but to note that, although an engineering triumph, it has resulted in few if any discernible "major beneficial political and social implications" of the type advertised by the one-way Mars mission proposal. If the tepid public reaction to the ISS is any indication, then it's not clear that such expectations should weigh in favorably in our evaluation of Schulze-Makuch and Davies's scheme to establish a human settlement on Mars post haste.

As with other motivations for the proposed expedited colonization of Mars - that it serve as a science outpost and as a lifeboat for humanity - rational analysis demands that we consider how alternative approaches compare as far as promoting a more positive political and social climate here on Earth. In other words, given that a one-way mission would cost hundreds of billions of dollars or more, how might similar - or even significantly smaller sums - be spent to foster feelings of union and brotherhood.

|

| Jimmy Carter tries to comfort a 6-year-old at Savelugu (Ghana) Hospital as a Carter Center technical assistant dresses her painful Guinea worm wound. |

|

| U.S. F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with a $110 million per unit cost |

Suffice it to say, we don't need to go shopping around for extraterrestrial projects, such as an ill-considered one-way mission to Mars, in order to concoct challenges to inspire and unify us, when working in broad international coalitions against terrestrial scourges, such as disease, hunger, global warming, not only would generate a much greater sense of unity and common purpose, but also would offer desperately needed material advances to billions of people here on Earth.

Part 5: One-Way Mission to Mars - Ethics Fail

One-Way Mission to Mars - Kumbaya Fail by Marc Merlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

One-Way Mission to Mars - Lifeboat for Humanity Fail

This is the second in a series of posts presenting my analysis and criticism of a proposed one-way mission to Mars. You can find the introduction here.

There goes the neighborhood

Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Paul Davies open their case for using a one-way mission to Mars to kick-start a human colony there by observing,

Asteroid deflection, survival on the cheap?

Subsurface habitats here instead?

With regard to an explosion of a nearby supernova, it should first be noted that humans on the surface of Mars may well suffer much the same fate as their counterparts on Earth. To the extent that specially designed subsurface human habitats on Mars would offer a significant amount of protection, then the same could be constructed on Earth and made available to a vastly larger number of people at a mere fraction of the cost of those used for a Mars colony.

Indeed the only reliable way to develop, verify and refine the kind of habitats to be used by one-way Martian colonists would be to design, build and inhabit comparable structures here. So, far from representing an additional cost, fully-functioning terrestrial habitats would appear to be a useful, if not a necessary, step in successfully engineering counterparts on Mars.

In addition, a permanent underground terrestrial communities manned by a multinational force, composed of volunteers serving staggered, limited-term tours of duty, not only would provide significantly more assurance of our survival as a species in the event of a catastrophe of astrophysical origin, but also would serve to promote exactly the kind of international cooperation that the authors state is one of the desirable side-effects of the effort to colonize the Red Planet.

Mars, a disease and discord free zone?

Other threats that motivate Schulze-Makuch and Davies include "global pandemics, nuclear or biological warfare, runaway global warming [and] sudden ecological collapse." Mars colonists would be placed at a safe remove from the first two types of these catastrophes, but would nonetheless be subject to the dangers posed by disease as well as to the kinds of political, not to mention interpersonal, discord that could lead to the annihilation of their "civilization" in a matter of minutes. On Mars a jilted lover with a hammer and access to critical life-support systems becomes that planet's Kim Jong Il.

As far as large-scale environmental degradation wrought by the likes of devastating climate change goes, it should be noted that even the most dreadful envisioned outcomes here would leave Earth-bound humans with an ecosystem infinitely more hospitable than any that they will ever find on Mars.

A lifeboat to nowhere

More generally, the problem with the portrayal of a Martian colony as a putative lifeboat for humanity is that, as a metaphor, it is all too apt. Lifeboats by their nature are transitional places of refuge; they are meant to convey passengers from a situation of rapidly deteriorating safety to one of predictable security; they are not sanctuaries in and of themselves. Far from it, lifeboats are risky environments, recommended only by the fact that the certainty of going down with the ship is a far less attractive option.

Such would be the case with human presence on Mars, founded imprudently as a falsely desperate one-way mission, a lifeboat continuously in peril and without the glimmer of a hope of ever reaching another shore.

Part 3: One-Way Mission to Mars - Science Fail

One-Way Mission to Mars - Lifeboat for Humanity Fail by Marc Merlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.

|

| Illustration of an impact event (courtesy of NASA) |

Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Paul Davies open their case for using a one-way mission to Mars to kick-start a human colony there by observing,

[W]e are a vulnerable species living in a part of the galaxy where cosmic events such as major asteroid and comet impacts and supernova explosions pose a significant threat to life on Earth, especially to human life.

and suggesting that it would offer humanity a "lifeboat" in the event of such mega-catastrophes.

Since recognition in the 1980s that the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event 65.5 million years ago that led to the demise of the dinosaurs was likely due to an asteroid impact, humanity - and Hollywood - have been put on notice that such "planet-killing" collisions are statistical possibilities, whose likelihood approaches a near certainty over time, that is without effective intervention.

Since recognition in the 1980s that the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event 65.5 million years ago that led to the demise of the dinosaurs was likely due to an asteroid impact, humanity - and Hollywood - have been put on notice that such "planet-killing" collisions are statistical possibilities, whose likelihood approaches a near certainty over time, that is without effective intervention.

Asteroid deflection, survival on the cheap?

Admittedly, having humans living on Mars would mean that some of our species would be safely out of harm's way in the event of such a catastrophe. Their long-term survival, though, would be far from certain. As a matter of prospective cost and potential benefit, the question is not whether a Mars colony, if successful, would guarantee that a few humans would survive for some period of time, since it does, but whether an expedited colonization program compares favorably with alternative approaches for accomplishing a similar or even vastly more desirable result.

For example, expanded investment in surveillance efforts - such as NASA's Near Earth Object Program - intended to identify potential collisions, coupled with the development of technologies to deflect space rocks heading our way by finessing their orbits years, if not decades, in advance of a too-close encounter would appear to be a immensely more cost-effective solution, one in which the survival not of 150 isolated souls on a cold, barren planet, but of billions of human beings on a globe teaming with life could be more predictably assured.

|

| Near-Earth asteroid discoveries as a function of time |

|

| Artist's conception of a Mars settlement with a cut-away view (courtesy of NASA) |

With regard to an explosion of a nearby supernova, it should first be noted that humans on the surface of Mars may well suffer much the same fate as their counterparts on Earth. To the extent that specially designed subsurface human habitats on Mars would offer a significant amount of protection, then the same could be constructed on Earth and made available to a vastly larger number of people at a mere fraction of the cost of those used for a Mars colony.

Indeed the only reliable way to develop, verify and refine the kind of habitats to be used by one-way Martian colonists would be to design, build and inhabit comparable structures here. So, far from representing an additional cost, fully-functioning terrestrial habitats would appear to be a useful, if not a necessary, step in successfully engineering counterparts on Mars.

In addition, a permanent underground terrestrial communities manned by a multinational force, composed of volunteers serving staggered, limited-term tours of duty, not only would provide significantly more assurance of our survival as a species in the event of a catastrophe of astrophysical origin, but also would serve to promote exactly the kind of international cooperation that the authors state is one of the desirable side-effects of the effort to colonize the Red Planet.

|

| Former NASA astronaut Lisa Nowak, charged with attempted murder |

Other threats that motivate Schulze-Makuch and Davies include "global pandemics, nuclear or biological warfare, runaway global warming [and] sudden ecological collapse." Mars colonists would be placed at a safe remove from the first two types of these catastrophes, but would nonetheless be subject to the dangers posed by disease as well as to the kinds of political, not to mention interpersonal, discord that could lead to the annihilation of their "civilization" in a matter of minutes. On Mars a jilted lover with a hammer and access to critical life-support systems becomes that planet's Kim Jong Il.

As far as large-scale environmental degradation wrought by the likes of devastating climate change goes, it should be noted that even the most dreadful envisioned outcomes here would leave Earth-bound humans with an ecosystem infinitely more hospitable than any that they will ever find on Mars.

A lifeboat to nowhere

|

| A scene from Alfred Hitchcock's 1944 film Lifeboat |

Such would be the case with human presence on Mars, founded imprudently as a falsely desperate one-way mission, a lifeboat continuously in peril and without the glimmer of a hope of ever reaching another shore.

Part 3: One-Way Mission to Mars - Science Fail

One-Way Mission to Mars - Lifeboat for Humanity Fail by Marc Merlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at thoughtsarise.blogspot.com.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)