As Director of the

Atlanta Science Tavern and a full-time science advocate of sorts, I frequently find myself wrestling with the question of how to communicate what is meant by the scientific consensus and why it should be trusted, especially in regard to the formulation of public policy.

|

| State of Fear book cover |

Often the issue comes up in a discussion in which one of he participants appeals to a single book or a limited set of studies as the definitive position to take on a complex and controversial science-related topic. The arguments appear compelling, and the supporting research seems well documented. Doesn't this place the burden on opponents, even if they subscribe to a view consistent with accepted scientific opinion, to read and critique these "killer" arguments?

This situation presented itself again recently as a result of a comment thread having to do with global warming on a Facebook group called "Rationals". One participant, who strongly doubted the reality of climate change, cited Michael Crichton's novel

State of Fear as the basis for her thinking. She also offered some intuitive, commonsense arguments against the claims made by climate scientists.

What follows, with some minor edits, is my response to her.

|

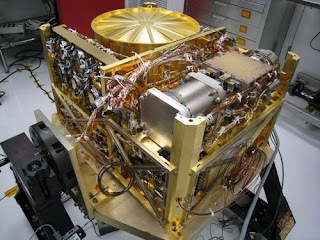

| IPCC Fourth Assessment Report |

If any document should be required reading for this discussion, I would suggest "Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2007" (

link). You may prefer the single chapter called "Summary for Policymakers".

Why do I suggest it instead of, say, Michael Crichton's

State of Fear? It's not because I have read Crichton's book - I haven't - or because I dispute his sources - I don't. It's because I could spend my life reading the variety of positions that various individuals and organizations hold concerning climate change. Even though I am relatively scientifically astute, I just don't have the expertise or the time to navigate all the competing claims.

The demand that one must read Crichton's book to engage in this debate "scientifically" is easily countered: require that anyone holding an a view opposing your own read all

your authors of choice. If this isn't a recipe for deadlock, I don't know what is.

So the question for me isn't whether Crichton is right or wrong. It is how does a discerning and intelligent lay person go about adopting a position on a controversial scientific topic, like climate change and its causes, which have significant public policy implications.

This is not an unfamiliar challenge. A public controversy swirls around the safety and effectiveness of childhood vaccines, and there are endless papers by "anti-vaccers" such

Andrew Wakefield and his supporters that are pointed to as required reading. Likewise with the teaching of the theory of evolution by natural selection in public schools. Here the "must read" opposing point of view includes all the Intelligent Design tracts issued by the creationist-leaning

Discovery Institute.

(I would note that these debates are rife with their own intuitive justifications, not unlike the one leveled at climate change scientists having to do with our "obvious" incapacity to model climate patterns over a period of decades. For anti-vaccination, the intuition is that vaccines containing mercury are "obviously" toxic. For the Intelligent Design community, commonsense supposedly tells us that certain biological processes are "obviously" too complex to have originated through natural processes.)

The answer to the question, from both a practical and an intellectual perspective, is that with such scientific controversies we seek to determine, to the best of our ability, whether there is a consensus in the scientific community.

For climate change and its causes the existence of such a consensus is indisputable. The vast majority of the thousands of researchers engaged in climate research agree with the findings of the IPCC. The same kind of consensus holds among experts in vaccine safety and evolutionary biology relative to challenges made by anti-vaccers and Intelligent Design proponents, respectively.

Does this mean that the scientific consensus about climate change is necessarily correct? No, it doesn't. Since all scientific claims are provisional, the ones made about climate change are subject to revision. But the fact of the matter is that policy making can't wait for "final" answers in urgent circumstances. We have to respond to threats, and we have to go with our best understanding of the situation, which, to a large extent, is another name for the scientific consensus.

Does this mean that contrarians and outliers are all kooks and nuts? Not at all. There is a small but concerted scientific opposition to climate change, but it appears as though that their ranks are dwindling. (See this recent

New York Times op-ed for an example). It does mean that the burden of proof has shifted dramatically to the opponents of accepted climate change science.

Finally, the question of the trustworthiness of the climate research community in general and the IPCC in particular has to be addressed. The thousands of scientists engaged in these studies represent dozens of countries and hundreds of research institutions. It's not clear what their objective would be in deliberately distorting the evidence and analysis underlying conclusions relative to anthropogenic climate change, but it would require a conspiracy of gargantuan proportions.

Having been a scientist at one time myself, I find the suggestion that these dedicated men and women are engaging in "group think" hardly convincing. Scientists revel in proving one another wrong. Although I do admit the gatekeepers of peer-reviewed journals might reflexively look askance at an outlying submission these days, I do believe that well-founded opposing points of view have seen the publication light of day. Scientists as a whole are a smart, honest and self-reflective lot when it comes to their work.

Of course the process of developing this climate change consensus has seen its own share of errors and even acts of malfeasance. What human endeavor on this scale hasn't? The good news is that the scientific process is self-correcting. This is why rational people find the process so trustworthy. It is skeptical of its own conclusions and committed - come hell or high water - to finding the best available explanations consistent with the evidence at hand.

Killer Arguments versus the Scientific Consensus

Killer Arguments versus the Scientific Consensus by

Marc Merlin is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Based on a work at

http://thoughtsarise.blogspot.com/2012/11/killer-arguments-versus-scientific.html.